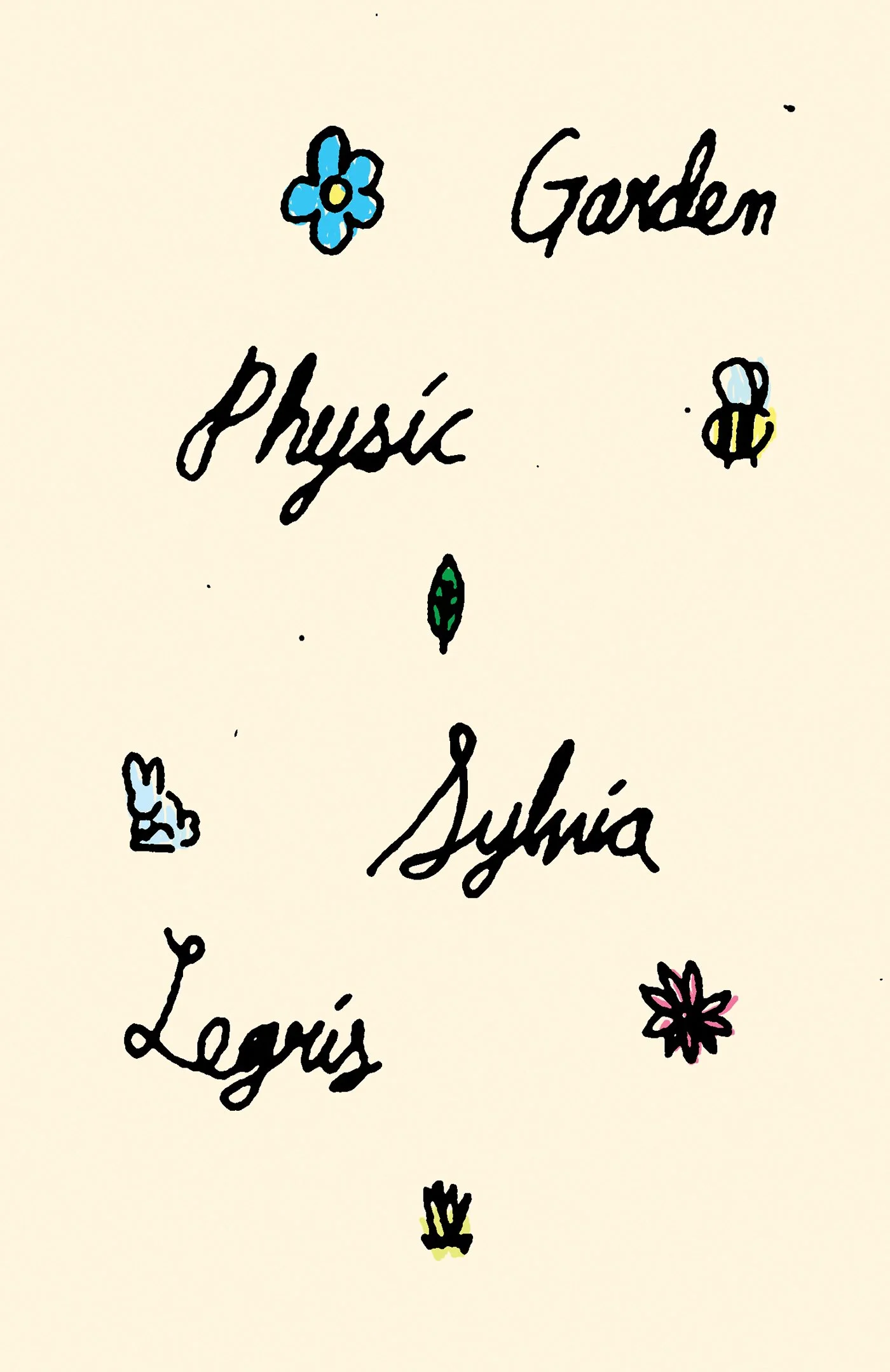

Sylvia Legris’s Garden Physic (New Directions, 2021)

By Elizabeth Greene

This is a dazzling book. From the opening section title, “The Yard Wants What the Yard Wants,” and great first line, “The flourish, the fanfare, the febrifugic feverfew,” the language in Griffin Prize winner Sylvia Legris’s, Garden Physic weaves and spins with wordplay, with unanticipated phrases and metaphors, with rolling lists, which can define a garden or a landscape, with unexpected rhymes and off-rhymes. The inventive language of this poetry is itself worth the trip.

But the language is only the beginning. Legris explores themes of gardening, love, healing, and poetry in four short sections, beginning with the opening, “Plants Reduced to the Idea of Plants” and “Plants Further Reduced to the Idea of Plants.” How do you turn life into art? Through herbariums, through woodcuts, through designs—here, William Morris’s designs. After this, in “The Garden Body: A Florilegium”, plants appear in abundance, tumbling over one another. Two lines stand out:

At the center of the garden the heart.

Red as any rose.

Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn all make appearances here (a link to Pedanius Dioscorides in the book’s fourth section) but roses are the heart of the garden, and where there are roses, there’s love. Rachel Pollack, one of the Tarot greats of our age, says, “There is no healing without Aphrodite.” No gardens, either.

The book’s third section, “Floral Correspondences,” imagines letters between famed gardener Vita Sackville-West and her husband Harold Nicholson. This correspondence turns through the gardening year, from “a disagreement between winter and spring” through “perpetual roses” to “diminishing light” to “midwinter / and poems are difficult as flowers.”

The titles, “My Darling,” “My Dear Love,” “Dearest,” as well as the intimate tone, indicate that this garden is rooted in love (we know Virginia Woolf lurks on the sidelines—that’s love too).

Astonishingly, Legris conveys the beauty and variety of the garden, the progress of the year, and the married intimacy, in thirteen short poems.

Poems drawn from Pedanius Dioscorides’s De Materia Medica, a first-century treatise on botany and pharmacology which remained authoritative for sixteen centuries, form the fourth and longest section of Garden Physic. This section emphasizes healing:

Pharmacy begins in plants.

Plants are the flesh of the Gods.

In the Kingdom of Nature the final authority is Earth.

Remedies are based on plants, earths, water, grime, and animal parts, including fox lungs, cockroaches, and earthworms. There is also a short poem on the origins of poetry, with the sections “Sepia” and “Ink”, reminding us that writing too begins with the natural world. The treatise is dedicated to “Dearest Aerius” and closes with a valediction to this loved friend.

By this time, the reader feels that she has been gardened every which way. But wait—there are the appendices! These include a map of the poet’s backyard garden, complete with birds, a description of the gardening process, and two visual poems: Pedanius Dioscorides quotations and William Morris designs superimposed on maps of Saskatchewan.

Garden Physic reaches far and deep but is always playful. You’ll leave it wanting to stick your hands in the earth—or at the very least, to buy a pot of blue hyacinths. This is a book that will change the way you see.

Elizabeth Greene is the author of A Season Among Psychics, a novel, and three collections of poetry. She edited We Who Can Fly: Poems, Essays and Memories in Honour of Adele Wiseman, which won the Canadian Jewish Book Award for Best Scholarship on a Canadian Subject, and The Dowager Empress: Poems by Adele Wiseman. She taught for many years at Queen’s University, ending her career with a course she originated on Contemporary Canadian Women Writers.